Basic Shell Interaction

Overview

Teaching: 20 min

Exercises: 30 minQuestions

How do we interact with a UNIX shell, the basic HPC interface?

What is a file system?

How do we navigate around files and directories from a UNIX shell?

How do we manage files and directories from a UNIX shell?

How do we work with text files from a UNIX shell?

How do we get help on UNIX shell commands?

Objectives

Navigating around files and directories

Managing files and directories: copying, moving/renaming, and erasing

Viewing and editing text files

Preparing files for the upcoming hands-on exercises

UNIX shell plays an important role in the user interaction with HPC systems. This episode serves as a crash course on UNIX shell and tools. What is presented here is short enough to allow newcomers to become quickly productive in the (apparently) clunky interface used in many HPC systems. Take heart: despite the archaic look, the tools are actually very powerful and will allow you to be very productive.

In this episode…

We will learn how to navigate file systems with

pwd,ls,cd; how to manage files and directories (create, copy, move/rename, delete) usingmkdir,cp,mv,rm,rmdir; view and edit text files usingcat,less,nano. We will also show you how to look for helpful documentation on these tools so that you can learn more about these commands and become effective in using them. There is a summary at the end of this lesson for your quick reference.

Login to Wahab First!

For this session, we assume that you have just logged in to Wahab HPC cluster. Please review the previous episode for instructions on how to connect to this cluster.

UNIX Shell: First Impression

On Wahab, the UNIX shell prompt looks like this:

[USER_ID@wahab-01 ~]$

This prompt tells you that you are interacting with a computer named wahab-01.

(Frequently, but not always, your user name is also shown on the prompt.)

We can also find this fact out by using the hostname command.

Type hostname followed by Enter, and see what comes out:

[USER_ID@wahab-01 ~]$ hostname

wahab-01

This type of interface with a computer is called

command-line interface (CLI).

You, as the user, give instructions to the computer

by typing commands (and optionally some arguments),

then press Enter (also known as Return)

to execute the command.

This read-evaluate-print loop (REPL) is the heart of a command-line interface.

Depending on the command, some output may be printed on the screen.

In the example above, the hostname produces a short string: wahab-01.

UNIX shell is a very basic CLI:

Without additional software,

the shell only accepts text from the keyboard as its input,

and only produce text as its output.

The combination of keyboard and text-based screen is often referred to as

terminal, and for our purposes, is equivalent to CLI.

Why Learning Command-Line Interface?

The vast majority of computer systems today have graphical user interface (GUI) with windows, images, and videos for output; whereas mouse, trackpad and touch screen are often used for input. CLI or terminal interface is a very old computer interface, dating back in 1960s.

You may wonder: Why do I need to learn to use an ancient CLI at all? As we shall see in this lesson, CLI allows computer users to become very effective and productive. Just by typing a few commands you are able to accomplish many actions that require many points and clicks on a GUI. Frequently used combination of commands can be saved into a script: just running this script will allow us to accomplish a large unit of tasks, and repeat them with ease. Next to CLI, scripting (the action of creating and using script) is another foundational matter in using a supercomputer—this will be covered in a latter episode.

Throughout this lesson, you will encounter many commands and examples on how to use them. Do not be afraid to try out and experiment with these commands—that is the only way to learn, become familiar, and eventually skilled with the CLI.

But wait! Will I damage the computer if I type a wrong command?

Good question! On a shared UNIX-like system like Wahab, there are plenty of protection measures that makes it very difficult for you to inflict fatal damages. For example, you are not able to delete or alter system files or files belonging to other people.

First Exploration with UNIX Shell

IMPORTANT

Please follow along all the commands shown below, as they are also meant to prepare your files for the hands-on exercises later on.

Just as your laptop computer, files on an HPC system are organized in terms of (sub)directories and files. (Some operating systems use the term “folder” for a directory; they are interchangeable.) The following illustration shows you representative directories and files on Wahab HPC (the layout on your specific HPC may vary):

In UNIX, there is only one filesystem, starting with the root directory

(/) as the top-level directory.

Directly under /, there are many directories.

We will explore some of these interesting directories shortly.

There are three life-saver commands on UNIX shell that you must always remember:

-

pwd(shorthand of “print working directory”) is the command to find out the current working directory of your shell. -

ls(shorthand of “list”) is a command to list the contents of the current working directory, or directory/file objects specified by the user. -

cd(shorthand of “change directory”) is the command to change the current working directory of your shell.

These three commands are essentially the most frequently used actions in a graphical file explorer (such as Windows Explorer or Finder): knowing where we are in a folder structure, changing folder, and listing the folder contents.

pwd — Print Working Directory

When you first log in to a computer,

you will be placed in your home directory.

To find out the location of your home directory,

we invoke the pwd command (sort for print working directory):

$ pwd

/home/USER_ID

USER_ID in the output above is just a placeholder

for your user ID on Wahab;

in your case, you will see your own user ID after /home/.

So, /home/USER_ID is your home directory.

(For ODU students and faculty, the user ID is the same as the MIDAS ID.)

Your home directory is denoted by the ~ character in the shell prompt.

This ~ is a common shortcut in UNIX, and is very useful in many instances

when working on a UNIX shell.

ls — List the Contents of a Directory

Use the ls command to list the contents of a given directory.

Used by itself, ls lists the contents of the current working directory.

Let’s try this now:

$ ls

This shows the contents of your home directory, which most likely is empty (which is often true for new HPC users).

Did I See Nothing … Or Not?

Unless you have been an existing HPC user and have created some files or transferred some files/directories into your home directory, you will see an empty output. Otherwise, you will see your own files and directories. For example, on the author’s home directory, ls gives the following output (truncated):

admin CItraining Consult Desktop HPC ... bin CLC_Data data-shell Documents hpc-analytics-1 ... BUILD CLCdatabases DeapSECURE Downloads hpc-analytics-2 ...(All these are directories that contain many other files and directories. We encourage you to use directories to organize your data in a way that’s logical to you.)

When invoking ls command,

you can specify the directory which you want to list the content of.

Let’s peek into the contents of the root (/) directory:

$ ls /

RC etc lib64 proc shared usr

bin home lost+found root snap var

boot initrd.img media run srv vmlinuz

cm initrd.img.old mnt sbin sys vmlinuz.old

dev lib opt scratch tmp

There are many objects in /—they can be either files or directories.

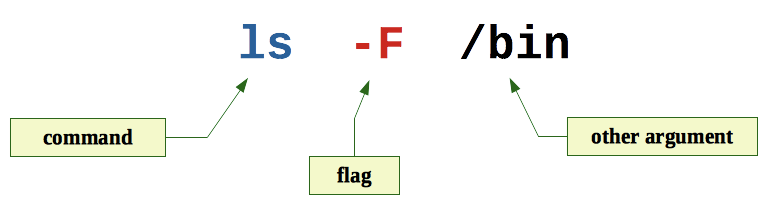

A more descriptive output can be given by adding the -F option

(also known as flag):

$ ls -F /

RC/ etc/ lib64/ proc/ shared/ usr/

bin/ home/ lost+found/ root/ snap/ var/

boot/ initrd.img@ media/ run/ srv/ vmlinuz@

cm/ initrd.img.old@ mnt/ sbin/ sys/ vmlinuz.old@

dev/ lib/ opt/ scratch/ tmp/

The slash (/) character appended after bin, dev, etc.

indicate that these objects are directories.

Other character indicators exist.

Most notably: * for executable files and @ for

symbolic links.

lsColorsOn modern HPC systems running Linux OS, most likely you will get a colored output with or without the

-Fflag, as an alternative indicator the type of the files/directories. This is a feature of a modernlscommand to improve command-line user experience. You can learn more about this in our extra lesson.

Activity: Touring the Cluster Filesystem

We already took a peek at the

/directory. Now let’s uselsto peek at some other directories on Wahab:

/bin/shared/apps/cm/shared/courses/DeapSECURE/home/USER_ID(your own home directory)/home/hpc-0081(somebody else’s home directory)If you can see additional directories inside, you’re welcome to browse further.

With someone sitting next to you, please answer the following questions:

- What do you see in each directory?

- Can you decide what each directory contains (e.g. what kind of files, what’s the purpose of that directory)?

- Do you have a directory you can’t see?

- Do you observe any problems with typing the directory name?

Solution

/bincontains executable programs, such aslsandhostname./shared/appscontains many programs that users can use on the cluster./cm/shared/courses/DeapSECUREis a shared directory containing datasets, programs, and exercise files for our workshop./home/USER_IDcontains, well, your own files./home/hpc-0081: You can’t read this directory usingls, because HPC system is designed to protect individual home directories such that only the owner can read and write files in his/her own home directory.In UNIX, file names are generally case-sensitive. This means that

/Binand/binare not equal.Please look deep inside

/cm/shared/courses/DeapSECURE/module-hpc/Exercises/Unixand answer the following questions:

- How many files end with

.txt?- What other file extension(s) do you see there?

Directory within Directory?

A directory is like an envelope that can contain other files (letters) and directories (other envelopes). Or it can be empty. For example, a directory named

/scratch/Workshops/DeapSECUREmeans that directory

DeapSECUREis contained within theWorkshopsdirectory, which in turn is contained withinscratch, which in turn is contained within the root (/) directory of the filesystem. This kind of nesting can go arbitrarily deep—subject to the operating system’s limitation.Suppose that one user has a

DeapSECUREwithin his home directory, e.g./home/tjones/DeapSECURETo refer to that

DeapSECUREdirectory, one has to specify which “bigger envelope” contains the directory (/home/tjonesor/scratch/Workshops). This is analogous to saying that to say that Mr. Thompson lives on 1800 Thomas Lane is not sufficient—we also need to specify the city and state.

File and directory names are case sensitive!

Please be aware that in Linux and UNIX, file names are case sensitive. For example, this means that

DeapSECUREanddeapsecureare not equal, and both names can exist in the same directory.

More About UNIX Commands

Each UNIX command comes with a rich set of options (or sometimes called flags)

that enrich the usability of the command.

For example, ls with the -l option tells a lot more information about each

file or directory printed.

$ ls -l /cm/shared/courses/DeapSECURE

total 60

-rw-r--r-- 1 wpurwant users 1422 Sep 30 11:04 README.DeapSECURE-workshops.txt

-rw-r--r-- 1 wpurwant users 1422 Sep 30 11:04 README.txt

drwxr-xr-x 6 wpurwant users 4096 Oct 5 00:17 _scratch

drwxr-xr-x 2 wpurwant users 4096 Sep 30 13:14 bin

drwxr-xr-x 7 wpurwant users 4096 Nov 14 2019 datasets

drwxr-xr-x 4 wpurwant users 4096 Oct 5 00:16 handson

drwxr-xr-x 2 wpurwant users 4096 Oct 5 07:36 lib

drwxr-xr-x 2 wpurwant users 4096 Oct 5 00:32 module-bd

drwxr-xr-x 2 wpurwant users 4096 Oct 5 00:32 module-crypt

drwxr-xr-x 2 wpurwant users 4096 Oct 4 23:54 module-hpc

drwxr-xr-x 2 wpurwant users 4096 Oct 5 00:32 module-ml

drwxr-xr-x 2 wpurwant users 4096 Oct 5 00:32 module-nn

drwxr-xr-x 2 wpurwant users 4096 Oct 5 00:32 module-par

drwxr-xr-x 4 wpurwant users 4096 Sep 30 17:05 src

drwxr-xr-x 4 wpurwant users 4096 Sep 30 17:06 tools

Each file is printed with the following attributes (let’s take

README.txt as an example):

- File attribute and permission bits (

-rw-r--r--) - Link count (don’t worry about this for now)

- File owner (

wpurwant) - File group (

users) - File size (1422 bytes)

- File modification time (September 30, at 11:04; the year is the current year, 2020)

- File name (

README.txt)

As you can see, directories have d as their first letter in the file attribute.

The -l option can be specified along with the file name.

(The typical UNIX convention specifies that flags need to come before the

file/directory arguments.)

Another important option is -a, which means “show all files”.

In UNIX, files whose names begin with a period are called hidden files;

they will not be printed by ls,

unless the -a option is given.

What’s in My Home Directory

Please perform

ls -aon your own home directory: What did you see?Solutions

On the author’s home directory, he finds:

. .emacs.d .mc .turing_tcshrc .. .fontconfig .mozilla .viminfo .bash_logout .gnome2 .ssh .wahab_bash_logout .bash_profile .gnupg .tcshrc .wahab_bash_profile .bashrc .history .turing_bash_history .wahab_bashrc .cache .ipython .turing_bash_logout .wahab_history CItraining .keras .turing_bash_profile .wahab_tcshrc .config .kshrc .turing_bashrc .Xauthority .emacs .lesshst .turing_historyThe precise answer would vary for your home directory—it partly depends on what you programs have launched so far on the cluster.

You may wonder why there are so many hidden files in your home directory. No, someone did not hack into your account and create these. Many hidden files are configuration files that you (end users) do not need to touch on daily basis. For example,

.bashrcand.tcshrcare configuration files for thebashandtcshshells, respectively.

cd – Changing Working Directory

UNIX shell and programs have the concept of current working directory.

This is the directory which the shell “thinks” as, well, its working directory.

For a given shell, there is only one working directory at any point in time.

The pwd command prints this working directory.

The cd command allows us change this working directory to a different one.

$ cd /

Explore Working Directory

After the last command (

cd /), please verify that your current working directory is indeed changed by invoking the __ command. Also, uselsto list the files/directories in the new working directory.Now use

cdandlsto go into the previously visited directories (from the previous hands-on activity) and see their contents again.

TODO Notice how the shell prompt changes as we change our working directory.

Too Much Typing? History and Tab to the Rescue

Feeling like typing too much already? Well, UNIX tool developers have put a lot of thought on making your life easier! There are three features of UNIX shell that are worth knowing:

Command history: The shell keeps a history of previously executed commands. To recall these, simply use the Up and Down arrow keys.

Tab completion: The shell’s input editor allows you to complete a partially typed word simply by pressing the Tab key. Depending on the context of the word, the shell will choose to complete it based on the available commands names, or file and directory names. We will demonstrate this feature below, as this is truly a keystroke saver.

Line editing: UNIX CLI relies completely on keyboard navigation. Mouse click will not change the position of the cursor. The Left and Right keys are used to move the cursor one character at a time. Use the Ctrl+A and Ctrl+E combination keys to jump to the beginning or end of the input line, respectively. (In many systems, the Home and End keys can be used as well.)

Tab Completion—Let’s say you want to change the current directory to

/scratch/Workshops/DeapSECURE/module-hpc. You begin by typing$ cd /sthen press the Tab. You will get several suggestions,

sbin/ scratch/ shared/ snap/ srv/ sys/(If the suggestions do not appear, you may need to press the Tab twice.) It partially completed the path to the longest possible common substring. Now you need to add more letter(s) to continue your input. Please append

corcr(don’t add any whitespace), then hit the Tab key again; the command line will become:$ cd /scratch/This is already a valid command, and the path is correct. But the directory is not yet the full path that we want.

Exercise

Keep completing the full path using the tab completion feature.

In the example above, you are trying to complete an argument to the

cdcommand. The shell was using the choices of files and directories that begin with/s.We can also do complete a command name. As an illustration, suppose we partially type

pyon a blank input line, then press Tab. You will get some choices:py3clean pygettext2.7 python3-jsondiff py3compile pygettext3 python3-jsonpatch py3versions pygettext3.6 python3-jsonpointer pyclean pygmentize python3-jsonschema pycompile pyhtmlizer3 python3.6 pydoc pyjwt3 python3.6m pydoc2.7 python python3m pydoc3 python2 pyversions pydoc3.6 python2.7 pygettext python3Since this is the first word of the statement, the shell looks for command names as the possible completion options.

While this explanation may look complicated, a little practice will help you get used to this tab completion facility. You will find that this little feature is such a tremendous keystroke saver!

More on UNIX Path and File Name

Absolute Path

The few examples with ls and cd above shows that

we can view (and access) any file and directory

located anywhere within the UNIX filesystem.

But so far, we do so by specifying the absolute path

of the file or directory—which, as you can tell, is very tedious.

An absolute path shows the way to get to a particular file from

the root directory, passing through all the intermediate directories,

like this one:

/cm/shared/courses/DeapSECURE/README.txt

An absolute path always begins with a leading slash. An absolute path leaves no room for ambiguity. For example, the following three paths are all distinct:

/cm/shared/courses/DeapSECURE/README.txt

/home/tjones/DeapSECURE/README.txt

/backup/projects/DeapSECURE/README.txt

But it involves a lot of typing; it is also error-prone.

Relative Path

Let us change directory to our shared training directory:

$ cd /cm/shared/courses/DeapSECURE/module-hpc

$ ls -F

Exercises/ geoip@ spams/

Both Exercises and spams are directories located within

module-hpc.

We can there peek into the contents of these directories

simply by using their base names (i.e. without any / character):

$ ls -F Exercises

Bandwidth_test/ Slurm/ Spam_bash/ Unix/ results/

$ ls -F spams

chmod.py Results_amp Results_par Results_seq Results_seq_alg2 untroubled@

That’s a whole lot shorter than writing the full absolute path

like /cm/shared/courses/DeapSECURE/module-hpc/Exercises!

Why? Because our current working directory is already where

Exercises is located.

A relative path gives the location of a file or directory

in relation to the current working directory.

Relative path is an alternative way to refer to a file or a directory, which is often much shorter than the absolute path. In the real world, you typically work with files and directories that are in your current working directory, or located only 1-2 subdirectories away. If your focus shifts to another group of files in a different directory, you can change to that directory before working on these files.

There are two magic directory names that always exist in every directory:

- A period (

.), indicating the current directory - A double period (

..), indicating the parent directory of the current directory

Example:

Understanding

.and..Our shell is currently at the

/cm/shared/courses/DeapSECURE/module-hpcdirectory. In this context,.refer to the same directory; whereas..refers to/cm/shared/courses/DeapSECURE.Other than the special meanings above,

.and..work just like any other relative path.

- From the current directory, what are the contents of

.and..directories?Solution

Exercises/ geoip@ spams/README.DeapSECURE-workshops.txt datasets/ module-crypt/ module-par/ README.txt handson/ module-hpc/ src/ _scratch/ lib/ module-ml/ tools/ bin/ module-bd/ module-nn/

- The subdirectory

/cm/shared/courses/DeapSECUREcontains other directories likemodule-cryptandmodule-par. How would you go to these directory using a singlecdcommand?Solution

Using absolute path:

$ cd /cm/shared/courses/DeapSECURE/module-cryptUsing relative path:

$ cd ../module-crypt

From the current directory

/cm/shared/courses/DeapSECURE/module-hpc, what would be the output ofpwdafter wecdto one of the following directories?

../.../..../../..../module-hpc./module-hpc(Clarification: These are not meant to be a sequence of relative directories to be

cd-ed in that order. Rather, only execute onecdin your mind, then think what would be the output of `pwd.)

Home Directory

Home directory is so important that it has

a magic directory name to denote it: ~.

We saw this already in the first shell prompt.

No matter where you are on the filesystem,

just invoke cd ~ to return to your home directory.

Even niftier: invoking cd command with no

argument will also return you to your home directory.

This is handy in many situations.

Finding Your Way Back to Home Directory

Starting from

/cm/shared/courses/DeapSECURE/module-hpc, which of the following commands could you use to navigate to your home directory, which is/home/USER_ID?

cd .cd /cd /home/USER_IDcd ../..cd ~cd homecd ../../../../home/USER_IDhomecdcd USER_IDSolution

- No:

.stands for the current directory.- No:

/stands for the root directory.- Yes:

/home/USER_IDis the absolute path of your home directory.- No: this goes up two levels, i.e. ends in

/scratch-lustre.- Yes:

~stands for the user’s home directory, in this case/home/USER_ID.- No: this would navigate into a directory

homein the current directory if it exists (otherwise, an error message would appear).- Yes: unnecessarily complicated, but correct.

- No:

homeis not a valid Linux command, therefore this will result in an error.- Yes: this is a special way to go to your home directory.

- No: There is no directory named

USER_IDin/cm/shared/courses/DeapSECURE/module-hpc.

Wildcards

UNIX shell has a pattern-matching capability to generate a list of files that match a given pattern. This is an important feature to allow bulk processing.

As an example, let’s start from the

/cm/shared/courses/DeapSECURE/module-hpc/Exercises/Unix directory.

This directory contains the following files:

cat1.txt clutter.sh garbage1.txt garbage4.txt hello.sh input3.txt

cat2.txt create.sh garbage2.txt garbage5.txt input1.txt my-ntoebok.txt

cat3.txt destroy.sh garbage3.txt garbage6.txt input2.txt Tutorial.txt

We can list only files that have the .txt extension:

$ ls *.txt

cat1.txt garbage1.txt garbage4.txt input1.txt my-ntoebok.txt

cat2.txt garbage2.txt garbage5.txt input2.txt Tutorial.txt

cat3.txt garbage3.txt garbage6.txt input3.txt

What Do These Pattern Do?

On the same directory, try the following and observe the result:

$ ls c* $ ls C* $ ls *m* $ ls *r* $ ls *r*sh $ ls cat?.txt $ ls *[135].txt $ ls *[2-5].txt $ ls *a[gl]* ls ../R*

When an argument has one or more of these special characters:

?, *, or a sequence enclosed by square brackets like [A-Z], [0-9],

[01234], the shell will treat this argument as

a pattern (sometimes called glob pattern).

It then searches for all file/directory names matching this pattern and

feeds the matching names to the command.

The special characters or the [...] sequences are called

a wildcard, and here are their meanings:

?matches a single, arbitrary character.*matches an arbitrary substring (zero or more characters).[135]matches a single character that can be a1,3, or5.[2-5]matches a single character that can be anything between2and5, inclusive.[AEIOU]matches a single character that can be aA,E,I,O, orU.[A-Z]matches a single character that can be anything betweenAandZ, inclusive.

It is the shell that does the matching and list generation,

not the ls command.

For example, with ls c*, the shell will look for all file/directory names

that begin with a c, and translate the statement to

ls cat1.txt cat2.txt cat3.txt clutter.sh create.sh

then execute the ls command.

Quoting an Argument

The shell treats the following characters as having special meanings:

| & ; ( ) [ ] { } < > ` ' " \ # * ~ $ ? ! =

The Space and Tab characters are also special.

If an argument really has to contain these special characters,

then the argument has to be quoted within

a pair of either single or double quotes.

The single quote does preserve all the characters literally,

whereas the double quote still does a few extra actions

with the $, !,

` (backtick),

and \ (backslash) characters

($ invokes variable value substitution, as we learn later).

Good Names for Files and Directories

Complicated names of files and directories can make your life painful when working on the command line. Here we provide a few useful tips for the names of your files.

Don’t use spaces.

Spaces can make a name more meaningful, but since spaces are used to separate arguments on the command line it is better to avoid them in names of files and directories. You can use

-or_instead (e.g.event-logs-2019/rather thanevent logs 2019/).Don’t begin the name with

-(dash).Commands treat names starting with

-as options.Stick with letters, numbers,

.(period or ‘full stop’),-(dash) and_(underscore).Many other characters have special meanings on the command line. We will learn about some of these during this lesson. There are special characters that can cause your command to not work as expected and can even result in data loss.

Sanitizing File Names

On GUI-centric platforms such as Windows, Mac, and Android, many users are used to using a whole gamut of characters in file names, which tend to cause trouble with UNIX way of processing. Here are some examples:

Member list.xlsxThesis revision 5 (backup).pptxTom & Jerry.txtQuestion #70.pdfCaution!Stocks valued above $10.xlsxHow should we quote these file names?

Solution

In all cases but the last two, one can use either single quotes or double quotes:

'Member list.xlsx'or"Member list.xlsx". In the last two cases, however, the!and$would invoke additional action with the double quotes; hence these names must be quoted with a pair single quotes for use in UNIX commands such as:$ ls -l 'Caution!' $ ls -l 'Stocks valued above $10.xlsx'

Editing Directory Content

Now that you have familiarity with location-based commands, let us learn how to edit directory contents. In this section, we will learn the following:

mkdir: creating new directories;cp: copying files and directories;mv: moving or renaming files and directories;rm: removing (deleting) files and directories.

Here’s our goal: we will create some new directories in your own home directory and copy the exercise files for our hands-on activities to this directory. We will also rename and delete some files.

IMPORTANT

We are going to use the directories created and the files copied below in the subsequent exercises. Please be sure follow along and do the commands in the light blue boxes below on your HPC account.

mkdir — Creating New Directories

Let’s create a directory called CItraining on your home directory,

then another one called module-hpc within that directory.

mkdir is the command to create new directories.

Preparing Our Hands-On Activities (Part 1 of 2)

Please follow along and invoke the following commands in this order:

$ mkdir ~/CItraining $ cd ~/CItraining $ mkdir module-hpc $ cd module-hpc

Review

What did we just do?

What does

~/CItrainingmean? What absolute path does this translate to?Use

pwdand check where your working directory is now.Solution

We just created a directory named

CItrainingin your home directory. We then created another directory namedmodule-hpcwithinCItraining.

- In the first

mkdir, we use an absolute path to specify the new directory’s name.- In the second

mkdir, we use a relative path instead.That little wiggle

~character stands for/home/USER_ID, therefore~/CItrainingactually stands for/home/USER_ID/CItraining.

- You can substitute

/home/USER_ID/in place of~/. This is necessary outside of the context of UNIX shell, as many programs actually do not know how to interpret the~at the beginning of a path name.- The

~/prefix is not necessary if you are already in the home directory.If all is well,

pwdshould give:/home/USER_ID/CItraining/module-hpc.

cp – Copy files and directories

The cp command is used to copy one or more files and/or directories.

Preparing Our Hands-On Activities (Part 2 of 2)

Check your current working directory first! Please make sure that it is

/home/USER_ID/CItraining/module-hpcbefore issuing the copying statement below. Otherwise, change to this directory, or make one if you don’t have it.Now we will copy the entire hands-on directory for this lesson so you have your own files to work on. DO NOT miss even a period.

$ cp -r /cm/shared/courses/DeapSECURE/module-hpc/Exercises/. .

Check the Result

- What does this

cpcommand do?- What files and directories get copied to your directory? Use

ls,pwd, and/orcdto find out.

The -r (recursive copy) option is powerful:

It allows us to copy an entire directory with subdirectories and files

contained therein.

Congratulations! You just copied this lesson’s hands-on directory with all the files and directories contained therein to your own home directory. Now we are ready to do some activities with files and directories.

Congratulations! You just copied this lesson’s hands-on directory with all the files therein to your own home directory. Now we are ready to hands-on involving files and directories.

The following activities show some capabilities of cp.

Let us go to the Unix subdirectory first.

Now create a directory called junk

then copy garbage1.txt and garbage2.txt to it:

$ cd Unix

$ mkdir junk

$ cp garbage1.txt garbage2.txt junk

The cp command has multiple possible syntax:

-

Making a copy of a single file to a new name (whether to the same directory or a different one):

$ cp garbage1.txt garbage7.txt $ cp garbage1.txt junk/garbage123.txt -

Making a copy of a one or more file(s)/directori(es) to a new directory (keeping the same name):

$ cp garbage1.txt junk/(The trailing slash is optional.)

-

Making a copy of an entire directory tree:

$ cp -r junk junk_backup

These syntax are fairly natural to our understanding:

by reading the statements above,

we can deduce what each cp invocation is trying to accomplish.

Copying Multiple Files

Now copy all files that begin with

garbageand ends with.txtto thejunkdirectory.Solution

There are many possible solutions, but the most compact statement would be:

$ cp garbage*.txt junk/Please double-check the

junkdirectory thatcpdoes what you want it to do.

mv – Moving and Renaming Files and Directories

Moving and renaming files and directories can be done using the mv command.

-

Renaming a single file. There is a typo in one of the file name—let’s fix that:

$ mv my-ntoebok.txt my-notebook.txt -

Renaming a single directory:

$ mv junk/ trash/Note that the destination name (

trash/) must not exist already. -

Moving one or more files to another directory:

$ mkdir data-in $ mv input*.txt data-in/This command also works to move a directory, or a combination of files and directories, as long as the destination directory (to which the other files/directories are moved) is mentioned last.

rm and rmdir – Deleting Files and Directories

The rm command deletes a file.

For example, all the garbage*.txt files are, well, garbage.

-

Deleting a single file:

$ rm garbage1.txt -

Deleting multiple files:

$ rm garbage*.txt

Warning: File Deletion is Permanent!

In the UNIX world there is no concept of “Recycle Bin” or “Trash Bin”. Once a file is deleted, it is permanently inaccessible. Therefore always perform

rmwith extra care!

The rmdir command can be used to delete an empty directory.

It refuses to delete a directory that is not empty.

For example:

$ mkdir meow

$ cp cat*.txt meow/

$ rmdir meow

rmdir: failed to remove 'meow': Directory not empty

How to do this, then?

$ rm meow/*

$ rmdir meow

In the example above we create a directory meow to contain the copy of

cat*.txt files.

To delete the meow directory, the files and directories inside it

must be removed first before rmdir can work.

Zapping an Entire Directory Tree

The vanilla rm command will not delete a directory:

$ mkdir meow

$ cp cat*.txt meow/

$ rm meow

rm: cannot remove `meow': Is a directory

But rm comes with the -r (recursive) flag

which can delete an entire directory tree:

$ rm -r meow

$ ls meow

ls: cannot access meow: No such file or directory

Warnings: Power Tools are Dangerous!

UNIX utilities are very powerful, therefore you must use them with some care. Here are some warnings:

Recursive copy (

cp -r): With recursive copy, everything in the source directory will be copied without warning. If the source directory has extremely large files and/or has many files, your can easily run out of storage. Therefore, know what you’re copying before executingcp -r.Remove (

rm) command: once a file is deleted, it is permanently inaccessible to you. Unlike GUI file managers like Windows Explorer or Finder, there is no recycle bin to retrieve the recently deleted files. (File recovery is actually possible, but it is extremely difficult operation that requires forensic tools.) In an HPC environment, you simply assume that the file is “gone” oncermremoves a file. Even more dangerous isrm -rcommand–it is deleting files and subdirectories specified in the argument.Asking Before Clobbering Files

The

cp,mv, andrmhas the-ioption to prevent accidental overwriting or deletion of files. If you are not sure whether you will clobber existing files, it is a good idea to include this option.

Viewing and Editing Text Files

UNIX terminal is also a useful interface to view the content of text files, as well as editing these files.

cat — Simple Viewing

The cat command simply concatenates the contents files given as input,

then outputs the result to standard output (i.e., the terminal).

If you provide one file the content of that file is displayed.

If you call cat without input, the command will print what you

type.

Some example uses:

In ~/CItraining/module-hpc/Unix, there are three files whose names

begin with cat:

$ cat cat1.txt

Life is an interesting adventure.

$ cat cat1.txt cat2.txt

Life is an interesting adventure.

If you like adventures then you probably like life.

It is full of surprises in both good and bad forms.

$ cat cat2.txt cat2.txt

If you like adventures then you probably like life.

It is full of surprises in both good and bad forms.

If you like adventures then you probably like life.

It is full of surprises in both good and bad forms.

$ cat cat3.txt cat2.txt cat1.txt

You can laugh, you can cry.

All this makes life interesting.

And that is why life is an adventure!

If you like adventures then you probably like life.

It is full of surprises in both good and bad forms.

Life is an interesting adventure.

less and more — Paged Viewing

less is a more sophisticated and versatile pager.

With less, you can view the file in both directions.

Basic Navigation with

less

- Up and Down: Scrolling up and down, one line at a time.

- Page Down or d or Space: Show the next page.

- Page Up or u or Backspace: Show the previous page.

- q: Exit

less.

The more command allows you only to view a file, one screen at a time,

in a forward manner.

You cannot go back.

The command terminates once the end of the file is reached.

more is an older and more primitive pager.

Our recommendation: whenever possible, please use the less command

because it is more powerful.

However, when you are in rare situation

where you do not have a fully functioning terminal or less is not available,

then more will be a useful tool to have.

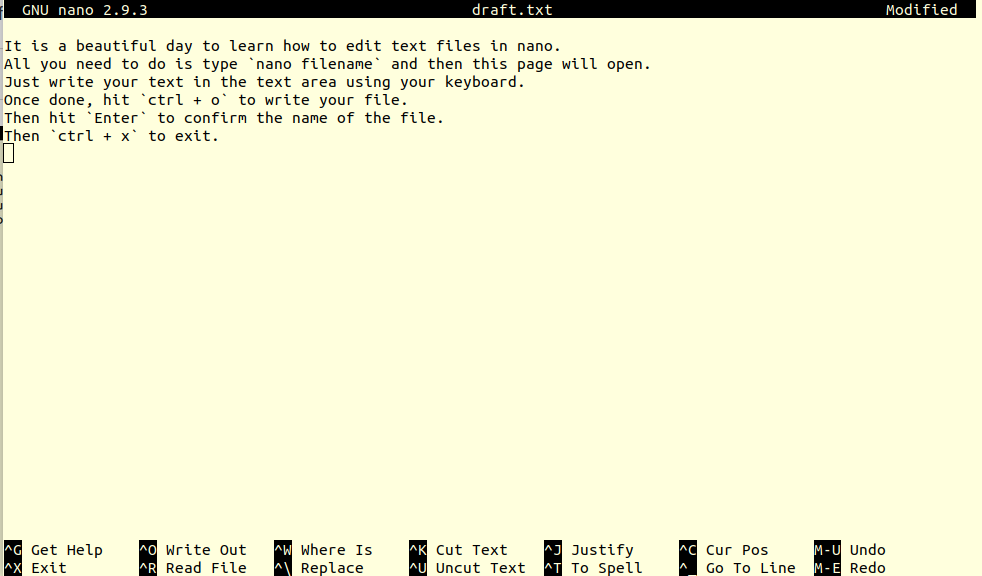

nano – Editing text files

Several text editors are popular in the UNIX-like world:

-

viand its more popular derivative,vim -

emacsand its derivatives (e.g.xemacs) -

nanoorpico

In this training module, we will focus on the nano text editor, because

it is a very lightweight open-source software, and

its availability is quite widespread (MacOS X and most Linux distributions

have it by default; whereas it is available for Windws in several ways–

one of which is through “Git for Windows” package.

Its interface is the most intuitive over all the other editor’s.

vi is the bread-and-butter editor for many UNIX users.

It is almost universally available on any systems running UNIX-like systems:

ranging from bare bone servers, Raspberry Pi (tiny computers), supercomputers,

cloud computers, etc.

However, its interface is terse and the learning curve is rather steep.

emacs is a good alternative editor.

Its interface looks somewhat similar to other text editors in the GUI world,

and there is a graphical interface for emacs if so desired.

However, its keyboard shortcuts are a different breed compared to what

many Windows or Mac users are used to.

Creating and Editing Text Files with nano

When working on an HPC system,

we will frequently need to create or edit text files.

Text is one of the simplest computer file formats,

defined as a simple sequence of text lines.

What if we want to make a file?

There are a few ways of doing this,

the easiest of which is simply using a text editor.

To create or edit a file, type nano [FILENAME], on the terminal,

where [FILENAME] is the name of the file.

If the file does not already exist, it will be created.

Let’s make a new file now, type whatever you want in it, and save it.

$ nano draft.txt

Nano defines a number of shortcut keys (prefixed by the Control or Ctrl key) to perform actions such as saving the file or exiting the editor. Here are the shortcut keys for a few common actions:

- Ctrl+O : saves the file (into a current name or a new name).

- Ctrl+X : exit the editor. If you have not saved your file upon exiting, nano will ask you if you want to save.

- Ctrl+K : cut (“kill”) a text line. This command deletes a line and saves it on a clipboard. If repeated multiple times without any interruption (key typing or cursor movement), it will cut a chunk of text lines.

- Ctrl+U : paste the cut text line (or lines). This command can be repeated to paste the same text elsewhere.

Editing Tryout

Please open the

cat1.txtfile and add a few lines of your favorite quotes. Save the file, exitnano, and view the contents usingcat,less, ormore.

Getting Help on UNIX Shell

How can you find more information about a UNIX command? How could someone on earth possibly remember all the options for these commands? There are at least three ways to find help:

-

Using the

--helpoption; -

Using the

man(manual) page; -

Using web search (e.g. Google, Bing, DuckDuckGo) to look for reference or tutorial.

In the following subsections we will touch each one of these.

Program’s Help Option

At least on Linux, many programs are equipped with the --help option

that will give you a (fairly brief) documentation on how to use the program.

For example: ls --help will give you an output like this:

Usage: ls [OPTION]... [FILE]...

List information about the FILEs (the current directory by default).

Sort entries alphabetically if none of -cftuvSUX nor --sort.

Mandatory arguments to long options are mandatory for short options too.

-a, --all do not ignore entries starting with .

-A, --almost-all do not list implied . and ..

--author with -l, print the author of each file

-b, --escape print octal escapes for nongraphic characters

--block-size=SIZE use SIZE-byte blocks. See SIZE format below

-B, --ignore-backups do not list implied entries ending with ~

-c with -lt: sort by, and show, ctime (time of last

modification of file status information)

with -l: show ctime and sort by name

otherwise: sort by ctime

-C list entries by columns

--color[=WHEN] colorize the output. WHEN defaults to `always'

or can be `never' or `auto'. More info below

-d, --directory list directory entries instead of contents,

and do not dereference symbolic links

-D, --dired generate output designed for Emacs' dired mode

-f do not sort, enable -aU, disable -ls --color

-F, --classify append indicator (one of */=>@|) to entries

--file-type likewise, except do not append `*'

--format=WORD across -x, commas -m, horizontal -x, long -l,

single-column -1, verbose -l, vertical -C

--full-time like -l --time-style=full-iso

-g like -l, but do not list owner

--group-directories-first

group directories before files.

augment with a --sort option, but any

use of --sort=none (-U) disables grouping

-G, --no-group in a long listing, don't print group names

-h, --human-readable with -l, print sizes in human readable format

(e.g., 1K 234M 2G)

--si likewise, but use powers of 1000 not 1024

-H, --dereference-command-line

follow symbolic links listed on the command line

--dereference-command-line-symlink-to-dir

follow each command line symbolic link

that points to a directory

--hide=PATTERN do not list implied entries matching shell PATTERN

(overridden by -a or -A)

--indicator-style=WORD append indicator with style WORD to entry names:

none (default), slash (-p),

file-type (--file-type), classify (-F)

-i, --inode print the index number of each file

-I, --ignore=PATTERN do not list implied entries matching shell PATTERN

-k like --block-size=1K

-l use a long listing format

-L, --dereference when showing file information for a symbolic

link, show information for the file the link

references rather than for the link itself

...

(The output was truncated because it was so long—more than 100 lines.)

A few things are worth mentioning:

-

Many options come with the short form (e.g.

-a) and the long form (--all). The long form are preceded by two dashes, and are useful when calling these commands from a scripts—they are long, but descriptive. -

Some options also have optional or mandatory parameters. For example, the

--formatwould be followed by a prescribed word, such asacross,commas,horizontal, etc. (see the documentation above). When using it forls, it has to be something like:$ ls --format=across $ ls --format=long $ ls --format=vertical

Reading a Command Syntax Specification

Near the top of this help text, the syntax of using the command is spelled out.

For ls:

Usage: ls [OPTION]... [FILE]...

For mv:

Usage: mv [OPTION]... [-T] SOURCE DEST

or: mv [OPTION]... SOURCE... DIRECTORY

or: mv [OPTION]... -t DIRECTORY SOURCE...

This syntax specification is key to correct utilization of these commands. Here are some help on how to read this syntax specification:

-

Usually, all-capital words needs to be substituted with the relevant values.

OPTIONrefers to any of the options listed in the help text. Something specified within square brackets, like[OPTION], means that the argument is optional (may or may not be given). Otherwise, it is mandatory. An elipsis means that what precedes it can be specified as many times as needed. For example: any of the following would be meeting thels [OPTION]...syntax specification:$ ls $ ls -a $ ls --all -l $ ls -a -l -c -

Other possible words:

FILE: any file (it can include a directory—please check the documentation)SRC,SRC_FILE,SRC_DIR: source file or directoryDEST,DEST_FILE,DEST_DIR: destination file or directoryCOMMAND: a valid UNIX command (program or built-in command)

man — UNIX Manual Page

On most UNIX/Linux systems, many programs come with a manual page

that can be read using man command.

Most of the time, you only need to know how to use a command

in its most basic form.

But if you are going beyond the basics and need to know an option

to do certain action, man can give you that.

Here is an example of the output of man:

$ man ls

LS(1) User Commands LS(1)

NAME

ls - list directory contents

SYNOPSIS

ls [OPTION]... [FILE]...

DESCRIPTION

List information about the FILEs (the current directory by default).

Sort entries alphabetically if none of -cftuvSUX nor --sort.

Mandatory arguments to long options are mandatory for short options

too.

-a, --all

do not ignore entries starting with .

-A, --almost-all

do not list implied . and ..

--author

with -l, print the author of each file

-b, --escape

print octal escapes for nongraphic characters

--block-size=SIZE

use SIZE-byte blocks. See SIZE format below

-B, --ignore-backups

do not list implied entries ending with ~

-c with -lt: sort by, and show, ctime (time of last modification of

file status information) with -l: show ctime and sort by name

otherwise: sort by ctime

-C list entries by columns

--color[=WHEN]

colorize the output. WHEN defaults to ‘always’ or can be

‘never’ or ‘auto’. More info below

...

At times, the output is often very similar to the --help output,

but often there are details in the manual page that are not mentioned

in the --help output.

man presents the documentation through a pager (e.g. less or more),

therefore one can navigate through the documentation up and down

and use the full capabilities of the pager.

Press q to quit the pager and return to the shell.

Internet Search

Internet sites and search engines can also provide us with information on

UNIX commands.

On your favorite search engine, type man ls or ls manual page.

Add UNIX or Linux if the first few hits are not what you want.

Several sites may turn up, such as:

(These websites are good ones that you can bookmark for future reference.)

The Shell Command Reference

Summary of Common UNIX Commands

Querying the shell’s current working directory:

$ pwdChange directory:

$ cd DIRList content of current directory

$ lsPaths

- Relative paths start in relation to a given directory such as current directory or parent directory.

- Absolute paths are given from root drive, starting with:

/- Home directory :

~- Current directory:

.- Parent directory:

..Create new directory

$ mkdir DIR_NAME | DIR_PATHCopy file:

$ cp [-p] SRC_FILE DEST_FILE $ cp [-p] SRC_FILE [SRC_FILE2 ...] DEST_DIROptional

-pflag preserves file modification time and permissions. The first syntax can be used to copy the file and create a new filename.Copy directory tree:

$ cp -r [-p] SRC_DIR DEST_DIRIf

DEST_DIRexist, then a subdirectory with the base name ofSRC_DIRwill be made to contain the copy; otherwise, the copy will be stored inDEST_DIR.Rename a file or directory:

$ mv SRC_FILE DEST_FILE $ mv SRC_FILE [SRC_FILE2 ...] DEST_DIR $ mv SRC_DIR DEST_DIRRemove file or directory

# Remove file rm FILE_NAME | FILE_PATH [FILE_NAME2 | FILE_PATH2 | ...] # Remove directory rm -r DIR_NAME | DIR_PATH rmdir DIR_NAME | DIR_PATHInspecting the content of a (text) file

$ cat FILE $ more FILE $ less FILE

- Use

catfor relatively short text file.morecommand allows pause between pages, but no scrolling backward.lessis the most sophisticated of all, allowing forward and backward scrolls, and more.Determining the type of a file

$ file FILEText editors for terminal

$ nano [FILE] $ vi [FILE] $ emacs [-nw] [FILE]

- New users are encouraged to use

nano, which is the easiest to use of all.viis the classic editor on UNIX platforms (it is actuallyvimon many modern Linux distributions).emacsis another favorite editor on UNIX-like platforms. The-nwoptional flag can be used to suppress the X11 GUI window of Emacs, if your SSH connection supports X11 programs.Command documentation

man$ man COMMAND

Key Points

UNIX shell provides a basic means to interact with HPC systems

pwd,cd, andlsprovides essential means to navigate around files and directoriesDirectories and files are addressed by their paths, which can be relative or absolute

Basic file management tools:

mkdir,cp,mv,rm,rmdirBasic text viewing and editing tools:

cat,less,nano